Let me hit you with something personal: Last year, I found myself alone in a room, TV blaring, scrolling through social media — surrounded by connection but feeling utterly isolated. Turns out, I wasn’t alone in that paradox. Studies show that even as we’re supposedly more ‘connected’ than ever, loneliness is reaching record highs. Now, add to that the decline of shared values, the rise of individualism, and our instinct to take the ‘easy road,’ and suddenly a sneaky question emerges: are we missing something fundamental? This post dives into juicy data, unconventional wisdom (thanks, Jordan Peterson), and even some biblical tales to chase down what we’ve lost — and how we might wrestle it back.

When Living Together Before Marriage Backfires (Wait, What?!)

It’s a common belief in modern relationships: if you live together before marriage, you’re giving your relationship a “test run.” Many people assume this approach will help you avoid relationship challenges down the road. But is that really true? Let’s look at what research and real-world experience suggest about living together before marriage—and why the easy road might not always lead to lasting love.

Challenging the Myth: Does Cohabitation Improve Relationship Odds?

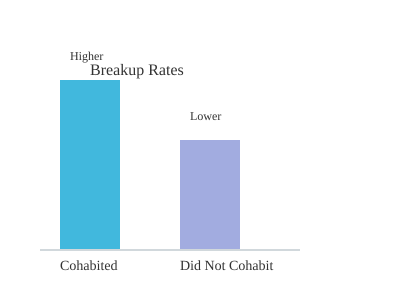

For years, you’ve probably heard that moving in together before tying the knot is a smart move. It seems logical—get to know each other’s habits, see how you handle daily life, and work out any issues before making a lifelong commitment. But research shows that this popular belief may be misleading. In fact, relationship breakdown statistics reveal that couples who cohabit before marriage actually face higher breakup rates compared to those who wait (see chart below).

“We know that couples who have lived together before the marriage actually increases the probability that the relationship will fail.” – Jordan Peterson (

0.00-0.04)

That’s a striking statement. And it’s not something you’ll often hear discussed in mainstream conversations about modern relationships. The idea that cohabitation could increase—not decrease—the risk of a breakup runs counter to what many of us have been told.

Why Taking the Easy Road Can Hurt Long-Term Bonds

So, why does living together before marriage sometimes backfire? According to Jordan Peterson (0.04-0.09), the answer is straightforward: avoiding risk and discomfort can actually harm your relationship. When you choose the path of least resistance—like moving in together to avoid conflict or to make life more convenient—you might be short-circuiting the deeper connection that comes from facing challenges together.

Think about it: real love isn’t just about comfort. It’s about growth, sacrifice, and sometimes, pain. If you never have to wrestle with tough decisions or work through disagreements, you might never develop the resilience needed for a lasting partnership. Peterson often emphasizes that love requires risk and discomfort. Without these elements, relationships can become stagnant or superficial.

Personal Anecdote: When Roommates Become Strangers

Maybe you’ve seen this happen. Two people move in together, hoping to build a stronger bond. But instead of growing closer, they start to drift apart. They avoid tough conversations, let small annoyances fester, and eventually become more like roommates than partners. Over time, unresolved issues pile up, and what started as an adventure turns into a silent standoff. It’s a scenario that plays out far too often in modern relationships.

The Adventure of Life: Why Challenge Matters

Life isn’t meant to be all smooth sailing. The adventure comes from facing obstacles, making sacrifices, and sometimes, feeling desperate enough to fight for what matters. Peterson points out that the easy access to things like sexual gratification (think: pornography) can short-circuit true connection (0.10-0.15). In a world that often values consumption over challenge, it’s easy to forget that lasting bonds are forged through struggle, not convenience.

Breakup Rates: Cohabitation vs. No Cohabitation

As the chart above illustrates, couples who lived together before marriage experience higher breakup rates than those who didn’t. While the numbers are hypothetical, they reflect a trend supported by relationship breakdown statistics and research findings. The takeaway? Sometimes, what feels like the safe choice can actually make things riskier in the long run.

The Comfort Crisis: Why Avoiding Conflict and Seeking Pleasure Leaves Us Lonely

Modern life is saturated with messages that encourage you to seek comfort, avoid pain, and chase pleasure at every turn. From endless scrolling on social media to the easy access of online pornography, the culture of consumption is everywhere. But what are the real side effects of this constant pursuit of ease? Let’s dig into a modern loneliness analysis and see how this consumption culture is quietly fueling an intimacy crisis.

Comfort as the New Goal: What Are We Losing?

If you look around, it’s clear that comfort and pleasure have become the ultimate goals for many. As Jordan Peterson points out in his interview (0.29-0.34), “we view ourselves as built for consumption and pleasure.” The logic is simple: if something feels good, do more of it. But research shows that this approach can actually undermine your motivation and weaken your social bonds.

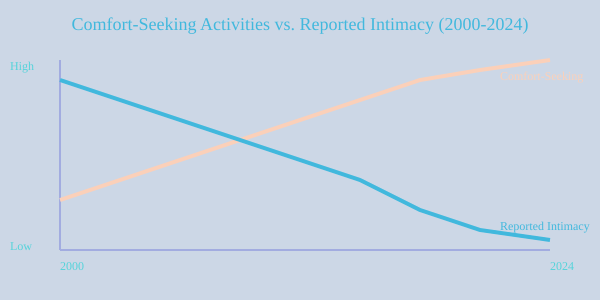

Consider the explosion of comfort-seeking activities—think about how much time is spent on social media or consuming adult content. These activities offer instant gratification, but they also make it easy to avoid discomfort, including conflict and emotional vulnerability. Over time, this avoidance can lead to dwindling intimacy, vanishing sex, and a disappearing sense of community.

Easy Gratification and the Downstream Cost

Peterson is blunt about the consequences of easy gratification (0.36-0.42): “It’s easy to get…sexual gratification, but does it matter? Oh, it’s a catastrophe. You’re not desperate anymore.” When you can fulfill your needs with a click, the drive to connect with others in meaningful ways fades. Studies indicate that high rates of pornography consumption and social media use are linked to reduced motivation for real-life connection and a growing sense of isolation.

This is the heart of the intimacy crisis. When you avoid conflict and seek only comfort, you miss out on the messy, challenging parts of relationships that actually bring people closer. The result? A society where loneliness is on the rise, even as we’re more “connected” than ever before.

Challengers vs. Consumers: Peterson’s Controversial Take

Peterson’s critique is sharp: modern society has become a culture of consumers rather than challengers (0.27-0.32). He argues that we’re built for maximal challenge, not for endless ease. In his words,

“If you’re going to have the true adventure of your life you’re going to need love, shame, guilt, desperation and pain.”

(0.44-0.49). It’s a controversial idea, but it raises an important question: could being “desperate” actually be a feature, not a flaw, in real love and adventure?

Personal Tangent: The Power of Discomfort

Think back to a heated family argument. Maybe it was uncomfortable, even painful. But sometimes, those moments of conflict lead to deeper understanding and stronger bonds. Avoiding discomfort might keep things easy, but it also keeps relationships shallow.

Chart: Comfort-Seeking vs. Intimacy Over Time

The more you chase comfort, the more you risk losing the very connections that make life meaningful. The comfort crisis isn’t just about personal habits—it’s about the future of love, identity, and community in a fragmented world.

Sacrifice, the Self, and the Paradox of Individualism

You live in a world that constantly tells you to “be yourself” and “find your own truth.” Yet, paradoxically, many people feel more isolated and adrift than ever before. This is the modern paradox of meaning and individualism: as the focus on personal freedom grows, so does the sense of collective identity crisis (0.51-0.53). It’s not just you—research shows that this tension is a widespread experience, especially in societies where traditional social structures are fading.

Jordan Peterson often points out that individualism only truly thrives when it’s anchored in shared values and robust social structures. If you try to build your identity on pure self-focus, you risk losing the very foundation that gives your life meaning. The importance of social identity isn’t just philosophical—it’s practical, affecting your mental health and sense of belonging (0.53-1.00).

Identity: More Than Just “Me”

Think about how your identity forms. It’s not just about your personal boundaries or your internal beliefs. Instead, your sense of self is a layered, hierarchical construct. You’re an individual, yes, but you’re also a spouse, a parent, a community member, a citizen, and—at the broadest level—someone who may seek connection with something metaphysical or Divine. This “clumping” of identity is natural and necessary (1.00-1.14).

Peterson uses the matryoshka doll analogy to illustrate this point. Imagine your identity as a set of nested dolls: the smallest is your individual self, surrounded by family, then community, then nation, and finally, the largest doll—your connection to universal or spiritual meaning. Each layer supports the others. If one is missing or weak, the whole structure can wobble.

| Identity Level | Description |

|---|---|

| Individual | Your personal traits, choices, and boundaries |

| Spouse/Partner | Your role in intimate relationships |

| Parent | Your responsibilities and identity as a caregiver |

| Community Member | Your place in local groups, workplaces, or neighborhoods |

| Citizen | Your connection to national identity and civic life |

| Metaphysical/Divine | Your search for ultimate meaning or spiritual belonging |

As you move through life, you might notice that your deepest joy and sense of purpose often come from these roles—not just from “being yourself” in isolation. In fact, losing the social scaffolding of these layers can lead to alienation, identity confusion, and a drifting sense of self. Studies indicate that mental health depends on harmony across all these identity layers, not just on internal belief systems (1.14-1.19).

“Your identity exists at all those levels… your mental health isn’t something you carry around in your head, it’s the harmony that exists or doesn’t exist between all those levels.” – Jordan Peterson

If you’ve ever felt lost or disconnected, it might not be a personal failing. Instead, it could be a sign that one or more layers of your social identity need attention. The importance of social identity and a strong mental health social structure can’t be overstated. Without them, the pursuit of meaning and individualism can leave you feeling empty, rather than fulfilled.

Hacking Happiness: The Surprising Science Behind Social Connection

When you think about happiness, you might picture achieving personal goals or finally feeling “at one” with yourself. But research shows that the real secret to lasting happiness isn’t found by looking inward—it’s found in your connections with others. The science of social connection reveals that having friends, being loved, and making sacrifices for others are far better predictors of mental health than simply achieving inner self-coherence (2.05-2.09).

It’s easy to forget just how social your mental health truly is. Consider this: solitary confinement is widely recognized as one of the harshest punishments, even for people who are already considered “antisocial.” This isn’t just a coincidence. It’s a stark reminder that humans are wired for connection. When you’re cut off from others, your sense of meaning and well-being quickly unravels (2.15-2.20).

Let’s take a step back and look at what happens when society becomes more individualistic. As the world grows more fragmented, there’s a temptation to see this as a positive—more freedom, more self-expression. But the flip side is alienation and isolation. The foundation that once held communities together has become shaky, and you can feel it in the rise of loneliness and the so-called “culture wars” (2.13-2.37). This is where the science of social connection comes in: it’s not just about you as an individual, but about the social structures that support your mental health (mental health social structure).

Here’s a personal example: Think about a time when you helped a friend out of a tough spot. Maybe you gave up your weekend to help them move, or you listened to them vent after a bad day. Chances are, you felt more fulfilled than if you’d spent that time ticking off a personal goal. That’s because making sacrifices for others—no matter how small—creates a sense of belonging and purpose that’s hard to replicate alone (sacrifice and happiness).

From a psychological perspective, studies indicate that self-consciousness is tightly correlated with negative emotions and suffering. In fact, the more you obsess about yourself, the more miserable you become. As Jordan Peterson puts it:

“The more you think about yourself, the more miserable you are.”

This isn’t just philosophical musing—psychometric data backs it up. Self-consciousness, one of the five major dimensions of temperament, tends to clump with misery and negative emotion. It’s a counterintuitive finding, but it’s true: focusing on yourself often leads to more suffering (self-consciousness and suffering).

Imagine if solitary confinement became the norm in digital life. What if every interaction was transactional, and you never truly connected with anyone? It sounds like a dystopian episode of Black Mirror, but it’s a real risk in today’s increasingly digital and isolated world. The antidote? Social “nesting” and self-sacrifice. These are the building blocks of happiness, according to social connection science.

| Key Dimension | Impact |

|---|---|

| Self-consciousness | Correlated with increased suffering and negative emotion |

| Social Structure Importance | Solitary confinement as extreme punishment, even for ‘antisocial’ individuals |

Ultimately, making sacrifices for others and building strong social ties are essential to feeling connected and fulfilled. Social integration and altruism aren’t just nice ideas—they’re the foundation of psychological health and happiness.

The Ladder to ‘The Good’: Chasing Meaning and the Divine in Modern Life

In today’s fragmented world, you might find yourself wondering what really gives life meaning. Whether you’re religious or not, the search for purpose is universal. The definition of the good—that ultimate value or aim—shapes how you set goals, make decisions, and even how you see yourself in the world. As Jordan Peterson points out, all of us, consciously or not, orient ourselves toward some idea of the highest good (4.25–4.32). This pursuit is at the heart of meaning in modern life.

Why Higher Meaning Matters—With or Without Religion

You don’t have to believe in God in the traditional sense to feel the need for something greater. Peterson describes how your identity exists on many levels: as an individual, a family member, a citizen, and even as part of a nation or culture (4.25–4.48). Each layer connects you to a broader sense of purpose. When these layers are in harmony, you feel mentally healthy and grounded. But when they’re fragmented, you can feel lost—“adrift in a storm, alone” (5.14–5.22).

The Hierarchy of Goals: Jacob’s Ladder Analogy

Peterson uses the image of Jacob’s Ladder to explain how we structure our lives. Think of your goals as rungs on a ladder, each one leading to something higher. There’s always another step, another aim, another challenge. This is the essence of a goal hierarchy: your daily tasks fit into larger ambitions, which in turn serve even bigger dreams. Research shows that positive emotion is closely tied to evidence of movement toward valued goals. In other words, you feel good when you’re climbing that ladder, no matter how high it goes.

Living As If There’s a Highest Value

Even if you’re not religious, you probably live as if there’s something that matters most—a “best imaginable aim.” Peterson calls this the Divine, not necessarily in a supernatural sense, but as a technical term for the ultimate motivating good. He puts it simply:

“The Divine is the good toward which all goods point.” – Jordan Peterson

This idea is central to both religion and personal development. It’s about orienting yourself toward what you believe is most worthwhile, even if you can’t define it perfectly.

The Moving Target: When Goals Recede

Here’s the conundrum: every time you reach a goal, a new one appears. Maybe you finally land your dream job, only to wake up a few weeks later and wonder, “Now what?” The pinnacle always recedes. This isn’t a flaw—it’s a feature of how humans pursue meaning. Our goals are nested within larger frameworks, and there’s no ultimate upper limit (6.00–6.12).

Choosing Goals When the ‘Good’ Is Unclear

You might not always know exactly what the highest good looks like. But even imperfect knowledge can point you in the right direction. Studies indicate that everyone, whether they realize it or not, orients toward some idea of the highest good. The process of aiming higher, of striving for something better, is what gives life its richness and depth.

In the end, your pursuit of meaning in modern life is shaped by the goals you choose and the values you hold highest. Whether you call it the Divine, the Good, or simply your best possible aim, it acts as a guiding star—helping you climb the ladder, one rung at a time.

What Now? Day-to-Day Choices That Reconnect Us to Each Other (and the Highest Good)

When you’re wrestling with meaning in a fragmented world, it’s easy to wonder: Can you actually do anything about all this, or are we just shouting into the void? The answer isn’t always obvious, but research shows that small shifts—tiny, daily meaning practices—can lead to big changes in your sense of purpose and well-being. Let’s break down how you can start finding purpose through actions that reconnect you to others and the highest good.

First, it helps to understand why you might feel anxious, frustrated, or even grief-stricken in the first place. According to Jordan Peterson (see transcript 6.14–6.24), negative emotions like anxiety and disappointment often cluster with self-consciousness. In fact, he notes that the more you think about yourself, the more miserable you are (6.55–7.00). Why? Because, as social beings, we’re wired to connect, not to isolate ourselves in endless self-reflection.

So, what can you do? Start with small, intentional actions aimed at service and meaning. For example, after a tough breakup, you might volunteer at a local dog shelter—not because it solves all your problems, but because helping someone (or some creature) else, just because, nudges you out of your own head. These are the kinds of small shifts that, over time, can create big changes in your outlook and sense of belonging.

If you’re more of a “lonely individualist,” try reframing your goals. Instead of asking, “What do I want?” consider, “What would I do if I always did what’s true and right?” This subtle shift in perspective moves your focus from self-centered desires to service and meaning—two things that research consistently links to greater well-being. As Peterson puts it,

“You might say, well, I don’t know what’s true and right… but it’s a very rare person who doesn’t know some of the time when they’re doing something wrong.”

(Peterson)

Another practical way to apply these ideas is to tweak your daily pursuits. Instead of obsessing over what you want, ask yourself, “Where would my effort help the most?” This could mean reaching out to a friend who’s struggling, joining a community group, or simply offering a kind word to someone who needs it. Even if you’re not sure what the “highest good” is, you almost always know when you’re moving toward—or away from—it.

Feeling stuck? Try this tangible experiment: For one week, focus on a single relationship or team. Make a conscious effort to support, listen, or simply be present. Notice what changes. Studies indicate that small daily choices in service of others or the ‘good’ can dramatically shift well-being. It’s not about grand gestures; it’s about consistent, meaningful action.

In the end, turning theory into practice is what matters. Orientation toward sacrifice, service, and truth isn’t just philosophy—it’s a set of daily meaning practices that help reweave both personal and collective meaning. And while it may be impossible to perfectly define the highest good, you almost always know some aspect of what’s right. Start there. Let your actions, however small, be the thread that reconnects you to others—and to purpose itself.

Conclusion: Wrestling Back Meaning, One Sacrifice at a Time

If you’re searching for meaning in modern life, you might think you need to make a grand gesture—move to a monastery, give up all your possessions, or embark on a quest for enlightenment. But research and lived experience suggest something far simpler, and perhaps more challenging: you need to reach beyond yourself, right where you are. The journey toward meaning and sacrifice doesn’t require perfection or dramatic change. It asks for small, imperfect acts—especially those that connect you with others.

Consider this: even the most antisocial people, including those labeled as psychopathic criminals, are deeply affected by social isolation (7.10-7.20). Solitary confinement is one of the harshest punishments because, as humans, our mental health and sense of meaning are tightly woven into our social fabric. In fact, your well-being depends more on your place within a social structure than on the internal consistency of your beliefs (7.25-7.40). This insight is crucial for anyone wrestling with meaning and sacrifice in a fragmented world.

Small Acts, Big Impact: The Power of Service for Meaning

You don’t have to overhaul your life to find more meaning. Instead, focus on small, daily acts of service for meaning. This could be as simple as helping a neighbor, listening to a friend, or volunteering for a local cause. Research shows that reconnecting to meaning is an ongoing, imperfect practice—one that happens in the context of small, social acts. It’s not about achieving a flawless state of happiness or enlightenment; it’s about the willingness to step outside your own concerns, even briefly, for the sake of someone else.

- Embrace challenge: Growth and meaning often come from doing what’s hard, not what’s comfortable.

- Serve others: When you give your time or attention, you reinforce your place in the social web that sustains mental health and happiness.

- Aim for higher meaning: Striving for something bigger than yourself—however imperfectly—can help heal the fractures of modern life.

The Paradox of Modern Life Happiness

Here’s a paradox worth considering: the less you fixate on your own happiness, the more it seems to find you. When you focus on meaning and sacrifice, happiness often becomes a byproduct. This isn’t just philosophical musing; it’s backed by studies indicating that those who serve others or pursue higher goals report greater life satisfaction.

Wild Card: Imagine the Ripple Effects

Imagine a world where every person made one daily sacrifice for someone else. What ripple effects would unfold? Would loneliness and fragmentation give way to connection and purpose? It’s a thought experiment, but it highlights the power of collective, small acts. Each sacrifice, no matter how minor, contributes to a larger story of meaning and belonging.

Ultimately, wrestling back meaning in a fragmented world isn’t about heroic leaps. It’s about realistic, imperfect striving—one small act of service at a time. You don’t have to be flawless, and you don’t have to do it alone. The path to modern life happiness is paved with everyday sacrifices, woven into the fabric of our social lives. And in those moments, you might just find the meaning you’ve been searching for.

FAQ: Your Burning Questions About Meaning, Identity, and Connection

When you’re searching for meaning in a fragmented world, it’s natural to have questions—sometimes the kind you might not even say out loud. This FAQ dives into some of the most common, practical concerns people face about love, identity, and the pursuit of the “good.” Drawing on insights from research and the source material (see timestamps 7.42–8.10), let’s explore these topics with direct, actionable advice that fits your everyday life.

Does living together before marriage really increase the risk of breakup?

This is a question that comes up often in relationship guidance. Research shows that couples who live together before marriage sometimes face a slightly higher risk of breakup, but the reasons are complex. It’s not just about cohabitation itself—factors like communication, shared values, and commitment matter much more. If you’re considering this step, focus on honest conversations about expectations and long-term goals. That’s where real relationship guidance begins.

How can I build a stronger identity if I feel lost or disconnected?

Feeling lost is more common than you might think. Identity help starts with small, intentional actions. Try reflecting on what energizes you, what you value, and who makes you feel most yourself. Even reaching out to a friend or joining a new group can be a step toward connection. As the transcript suggests (7.42–7.47), having people who care about you—and for whom you care—can anchor your sense of self. You don’t have to figure it all out at once; identity is built over time, not in a single moment.

What does ‘sacrifice’ mean in real terms for daily life?

Sacrifice isn’t always grand or dramatic. In fact, the transcript (7.51–7.57) points out that making sacrifices for others is deeply tied to meaning. This could be as simple as listening to a friend when you’re tired, or giving up a small comfort to help someone else. These everyday acts of giving are what strengthen relationships and build a sense of purpose—no need for heroics, just genuine care.

Can I find meaning without religion or belief in God?

Absolutely. Meaning without religion is not only possible, but common. Many people find purpose in relationships, creativity, nature, or helping others. The transcript (8.01–8.10) discusses the role of sacrifice in religious stories, but you can apply these principles in secular life too. What matters is living in a way that feels significant to you, whether or not faith is part of your journey.

Is obsessing over self-improvement sometimes counterproductive?

Yes, it can be. While growth is important, research indicates that relentless self-critique can actually undermine well-being. Sometimes, the best identity help is to pause and appreciate where you are right now. Balance striving with self-compassion.

What is ‘the highest good’ supposed to look like for regular people?

It’s easy to get caught up in lofty ideals, but the highest good is often found in small, consistent acts of kindness and honesty. You don’t need to change the world—just start with your corner of it.

How do I start reconnecting if I’m feeling desperately alone right now?

If loneliness is weighing on you, remember that even a single message or call can be a lifeline. The transcript (7.42–7.47) reminds us that having just one person who cares makes a difference. Reach out, even if it feels awkward. You’re not alone in feeling alone.

Quick tip: Is there a small change I can try this week?

Try one simple meaning tip: do something kind for someone else, no matter how small. Research shows that acts of kindness boost both your mood and your sense of connection. Sometimes, that’s all it takes to start moving toward meaning, identity, and the good you seek.

TL;DR: Modern life tempts us toward isolation and comfort, but true meaning may lie in embracing sacrifice, building strong bonds, and aiming at something higher than ourselves.

A big shoutout to The Diary Of A CEO for the valuable insights they offer. Be sure to take a look here: https://youtu.be/Hik6OY-nk4c?si=cbGGeXSBZgKdF2a-.