There’s this quote I once heard: ‘Business is war without bullets.’ But after listening to an ex-CIA officer, I realized the reverse is just as true — war, at its core, is business with higher stakes. Whether you’re closing a deal or running a covert operation in hostile territory, success hinges on psychology, negotiation, and a knack for uncovering the truth others would rather keep buried. Let me tell you about Mike Baker — a man who’s lived both worlds, in boardrooms and back alleys. You’re about to see how spycraft’s dark arts don’t just shape world events; they might already be shaping your next business move.

Where The World Is Now: New Cold Wars or Old Shadows?

If you take a step back and look at the world map today, the landscape of geopolitical threats in 2024 feels both familiar and unsettlingly new. You might hear experts say,

“China is at war with the West already — we just don’t see it.”

(0:00–0:03). This isn’t the kind of war with tanks and missiles you see in history books. Instead, it’s an invisible conflict, fought in boardrooms, cyberspace, and through subtle influence campaigns. The tension between China and Western nations is escalating, but it’s often hidden from public view (0:00–0:20).

When you scan the headlines, it’s not just the China vs West conflict dominating the conversation. Russia’s leadership, especially under Vladimir Putin, continues to cast a long shadow over global security. Nuclear threats are no longer relics of the past. Putin’s nuclear rhetoric is referenced repeatedly in intelligence circles and media reports (0:09–0:11). At the same time, Russia’s involvement in political assassinations—sometimes even targeting Western leaders—raises alarms across the globe (0:13–0:17).

But the complexity doesn’t stop there. Iran’s nuclear capability is a growing concern, with its program becoming a pressing intelligence target for Western agencies. The Iranian regime’s ambitions add another layer of uncertainty to an already volatile mix of threats. Research shows that these dangers are not just coming from traditional state actors. Non-state groups, cybercriminals, and shadowy networks are all part of the equation now. The challenge? Identifying the single biggest threat is as difficult as countering it.

You might wonder, who is the real enemy of the West? Is it Russia, China, Iran, or perhaps something more elusive—like the West’s own strategic missteps? The ambiguity is real. As discussed by former CIA officers and security analysts, the West is still struggling to define its adversaries clearly (0:17–0:20). This confusion complicates efforts to build effective strategies and can leave critical threats underestimated or even ignored by the public.

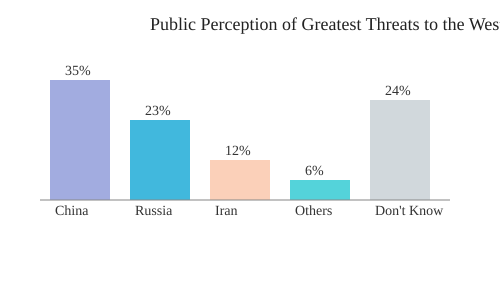

Assassination plots, nuclear escalation, and covert operations are not just the stuff of spy novels. They’re real issues that continue to unsettle global stability. According to recent surveys and speculation, public perception is split on which nation or group poses the greatest threat to the West. Many people simply don’t know, which highlights how much of this conflict remains hidden or misunderstood.

As you can see, the world’s most pressing threats are not always clear-cut. The lines between old Cold War shadows and new, invisible wars are blurring. And for analysts and policymakers alike, the haunting question remains: How does this end?

Spy Games: What CIA Tradecraft Teaches About Business Survival

When you think of CIA spy techniques, you probably imagine shadowy figures, coded messages, and high-stakes espionage. But what if those same skills could give you an edge in the boardroom? Former CIA officer Mike Baker spent decades perfecting the art of intelligence gathering, only to discover that these methods are just as effective in business as they are in the field (0:31–0:41).

At its core, the CIA’s business is all about harvesting actionable intelligence. Without reliable information, you simply can’t make smart, strategic decisions—whether you’re protecting national security or steering a company through a competitive market (0:47–0:51). That’s why, when Baker left the CIA, he found himself using the same business intelligence skills for companies that he once used for the government (0:42–0:45).

From Espionage to Business Consulting: Why the Transition Works

Why do these skills transfer so well? It comes down to the psychology of persuasion. In the world of espionage, you’re often tasked with convincing someone to commit the ultimate act of betrayal—treason. That’s a tough sell. But as Baker puts it:

“If you can sell the idea to somebody that they should commit treason on their country … that’s an incredible skill to use in business.”

Convincing someone to buy into your business vision, to switch loyalties from a competitor, or to trust you with sensitive information isn’t so different. Both require a deep understanding of human motivation, risk, and reward (0:53–1:00).

Targeting, Manipulation, and the Psychology of Persuasion

Let’s break down the core CIA spy techniques that translate directly into business intelligence skills:

- Targeting: Identifying the right person or opportunity to pursue.

- Manipulation: Influencing decisions and perceptions to your advantage.

- Psychology: Understanding how people think and what drives them.

- Identifying Weaknesses: Spotting vulnerabilities in competitors or negotiations.

- Closing the Deal: Bringing all your insights together to secure a win (1:09–1:19).

Research shows that the skills used in espionage—especially recruitment and negotiation—are directly transferable to business development. The ability to read people, anticipate their moves, and leverage subtle cues can turn a routine sales pitch into a game-changing opportunity.

Gathering Insights and Exploiting Leverage

In both espionage and business, gathering insights is about more than just collecting data. It’s about identifying weaknesses, exploiting leverage, and knowing when to make your move. The psychology of persuasion plays a huge role here. You need to know what motivates your target, what keeps them up at night, and how you can offer a solution that feels irresistible (1:17–1:20).

Getting Off the X: The Secret to Business Longevity

One of the most valuable lessons Baker took from his time in the CIA is the concept of “getting off the X.” In spy terms, the “X” is the danger zone—the place where you’re most vulnerable. In business, it’s about avoiding complacency and staying agile. Companies that master this mindset can build client relationships that last decades—just like undercover agents who maintain their cover for years (1:22–1:26).

| Skill | Description | Source Timestamp |

|---|---|---|

| Targeting | Identifying key opportunities or individuals | 1:09–1:11 |

| Manipulation | Influencing outcomes and decisions | 1:13–1:15 |

| Psychology | Understanding motivations and behaviors | 1:15–1:17 |

| Identifying Weaknesses | Spotting vulnerabilities to exploit | 1:17–1:18 |

| Closing Deals | Securing agreements and partnerships | 1:18–1:19 |

| Long-term Client Retention | Maintaining relationships for 20+ years | 1:24–1:26 |

Ultimately, the same CIA tradecraft that once shaped global events now underpins high-stakes business deals, from closing clients to negotiating with rivals. The overlap is surprising—and, as it turns out, incredibly useful for anyone looking to survive and thrive in today’s competitive landscape.

A Day in the Life: What Being a Spy Really Looks Like (And Why It’s Not Like the Movies)

If you imagine the daily routine of a CIA officer as a whirlwind of car chases, tuxedos, and high-tech gadgets, you’re not alone. But research shows that the real CIA officer daily routine is far less glamorous and much more complex. In fact, it’s often unpredictable, sometimes mundane, and always shaped by the demands of global intelligence operations. Let’s pull back the curtain and see what life undercover actually looks like, using insights from former CIA officer Mike Baker (2:06–6:38).

Living Abroad: The Overseas Reality

Most CIA officers spend significant time overseas—sometimes their entire careers. Mike Baker, for example, never had a headquarters job. “I spent all my time overseas,” he explains (4:12–4:23). You might find yourself living in a foreign country for two or three years, fully immersed in the local culture, or you could be on a short, one-off mission that lasts just a few days. As Baker puts it:

“You could end up living in a foreign country for two or three years … other times it could be a short, one-off operation.” (4:43–4:50)

These extended assignments mean you’re not just passing through—you’re building a life, setting up a home, and learning to blend in. The ability to adapt quickly is essential, as the nature of global intelligence operations requires constant operational flexibility.

What Does a Day Look Like?

Forget the movie scenes of endless action. In reality, your day might swing between seemingly ordinary tasks and moments of high tension. The CIA officer daily routine often includes:

- Meeting with assets (recruited sources) in covert locations

- Conducting surveillance—sometimes for hours, often unnoticed

- Writing detailed reports for headquarters

- Blending into the local environment to avoid detection

- Juggling personal relationships and maintaining your cover story

Research indicates that effective intelligence work involves extended overseas assignments and constant adaptation to new operational environments. You’re always on alert, always adjusting.

Officers vs. Assets: Clearing Up the Confusion

There’s a common misconception about the word “agent.” In the CIA, you’re actually called an officer. The “agent” or “asset” is the person you recruit—a source who provides information. As Baker clarifies (5:10–5:18):

- CIA Officer (Case Officer): The American running the operation

- Asset: The recruited source, which could be anyone from a government official to a cab driver with valuable local knowledge

The asset recruitment cycle is a core part of your job. It involves spotting potential sources, developing relationships, recruiting them, and then “running” them—managing the flow of information and ensuring their safety.

The Stress of a Dual Life

Maintaining a dual identity is one of the most challenging aspects of life undercover. You’re constantly balancing secrecy with the need to build genuine relationships. This can be stressful and isolating, as you can’t always share the truth with friends or even family.

Assets come from all walks of life, and their recruitment is rarely glamorous. Sometimes, the most valuable information comes from the most unexpected sources. You might spend months building trust, only to have an operation fall apart at the last minute.

Ultimately, the real world of global intelligence operations is about patience, adaptability, and the ability to operate in the shadows—far removed from Hollywood’s version of spycraft.

The Anatomy of Betrayal: Why People Turn, and How Spies Find Their Leverage

When you hear about espionage, it’s easy to picture high-tech gadgets and shadowy meetings. But at its core, the asset recruitment cycle is a deeply human process—one that relies on understanding the psychology of persuasion and the raw motivations that drive people to betray. Whether in the world of intelligence or corporate espionage tactics, the anatomy of betrayal is both art and science.

The Asset Recruitment Cycle: From Spotting to Running

The process starts long before any secrets change hands. According to the transcript (6:29–6:39), the asset recruitment cycle unfolds in distinct phases:

- Spotting: Identifying potential targets—anyone from foreign ministers to taxi drivers (6:16–6:21).

- Targeting: Assessing vulnerabilities and access.

- Development: Building a relationship, slowly crossing the trust threshold.

- Recruitment: Making the ask, setting the hook.

- Running: Managing the asset, collecting information, and maintaining the relationship.

But the clock starts ticking the moment an asset is recruited (7:06–7:16). The psychological toll of betrayal can quickly corrode a person’s character, making the recruitment window temporary and fraught with risk (7:13–7:22).

Motivation for Betrayal: The Real Drivers

What makes someone cross the line? Research shows that pinpointing and leveraging motivations is the heart of both recruitment and sales success. The transcript makes it clear: motivations are rarely ideological (12:12–12:17). Instead, they’re often personal and sometimes painfully simple (12:01–12:36):

- Money: The most common driver. Financial incentives are powerful, especially when someone is in debt or wants a better life.

- Family and Health: Sometimes, it’s about getting treatment for a sick child or helping loved ones.

- Ego and Resentment: Feeling overlooked, underappreciated, or slighted by an employer can push someone over the edge.

- Ideology: Surprisingly rare. Most betrayals aren’t about grand beliefs, but personal needs.

As one former CIA officer put it,

“To be able to convince somebody—sell the idea—that they should essentially commit treason … is a remarkable thing.”

The Psychology of Traitors: Lessons from History

Cases like Howard, Nicholson, and Hansen (9:55–10:15) show how devastating long-term betrayals can be. These individuals weren’t just betraying their country—they were betraying colleagues, friends, and families. The psychology of traitors is complex, and understanding it is crucial for anyone involved in corporate espionage tactics or intelligence work.

Managing Assets: The Need for Flexibility

Asset handlers must be prepared for abrupt handovers as assignments change. Building trust is delicate, but sometimes, you have to step away and let another handler take over (9:29–9:33). If you don’t understand the person’s motivation, it’s almost impossible to “close the deal”—whether you’re recruiting a spy or closing a business sale.

Chart: Frequency of Asset Motivations

This chart illustrates, based on anecdotal evidence from the transcript, how motivations like money and family needs far outweigh ideology in the asset recruitment cycle.

Beyond James Bond: Real-World Counterintelligence Disasters and What They Teach Us

When you think of espionage, it’s easy to picture the glamour and gadgets of James Bond. But the real world of counterintelligence is far messier, filled with betrayal, human error, and devastating consequences. In fact, some of the most damaging counterintelligence failures in history have come not from external threats, but from trusted insiders—people who knew the system inside and out. These stories aren’t just cautionary tales for intelligence agencies; they offer vital business security lessons for anyone concerned about insider threat detection and corporate espionage tactics.

Meet the Real Traitors: Ames, Hanssen, and More

Let’s start with the names that haunt U.S. intelligence: Aldrich Ames, Robert Hanssen, and Jim Nicholson. These aren’t just characters in a spy novel—they’re real people who managed to fool the system for years. As discussed in the transcript (9:55–10:05), these moles weren’t always recruited by foreign adversaries. Sometimes, as in Hanssen’s case, they proactively offered their services, leveraging their insider roles to devastating effect (10:43–10:53).

How Insider Knowledge Enabled Moles to Evade Detection

What made these individuals so effective? It wasn’t just access to secrets—it was their deep understanding of how counterintelligence worked. Hanssen, for example, was a longtime FBI agent responsible for counterintelligence related to the Soviet Union and Russia (10:09–10:10). He knew exactly how the system operated, which allowed him to betray U.S. interests for years without being caught (10:09–11:10). He even maintained a remote relationship with his Russian handlers, keeping his identity hidden and controlling the flow of information (10:53–11:03).

Disastrous Consequences: Only Discovered After the Damage

One of the most sobering realities is that counterintelligence teams often only learn of betrayal after catastrophic consequences. In Hanssen’s case, multiple Russian assets were compromised, with tragic results (11:06–11:10). The fallout from these counterintelligence failures is rarely contained to the agency alone. As one expert put it,

“They’re not just betraying their country … they’re betraying their family, service, and themselves.”

This multi-layered betrayal (11:20–11:29) underscores the human cost of insider threats—something that resonates far beyond the world of espionage.

Human Fallibility and System Flaws: The Real Weak Links

Research shows that failure to detect internal threats can have catastrophic consequences, not just in intelligence but in business as well. The most effective traitors weaponized their insider roles, exploiting both human fallibility and system flaws. No amount of technology can fully replace the need for human insight and vigilance. Counterintelligence isn’t just about monitoring—it’s about understanding people, relationships, and the subtle warning signs of betrayal (9:29–9:43).

Business Security Lessons from Espionage Failures

What does all this mean for you, especially if you’re in the corporate world? The parallels are striking. Corporate espionage tactics often mirror those used by state actors. Insider threat detection isn’t just an IT problem; it’s a human problem. Lessons from these espionage failures translate directly to business security. You need to build systems that account for both technical and human vulnerabilities. Trust, but verify. And never underestimate the damage a single insider can do if left unchecked.

| Case | Role | Duration Undetected | Assets Compromised | Source Timestamp |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robert Hanssen | FBI Agent, Counterintelligence | Long-term | Multiple Russian sources | 10:09–11:10 |

| Number of Moles | Howard, Nicholson, Hansen | — | — | 9:55–10:05 |

Ultimately, counterintelligence failures remind us that the greatest threats often come from within. Whether you’re protecting national secrets or corporate assets, understanding the human element is key to effective defense.

Lessons for Everyday Leadership: How the Spy Mindset Can Transform Teams, Negotiations, and Decisions

When you think about leadership strategies, you might picture boardrooms, not back alleys. Yet, the world of espionage offers a surprising toolkit for business psychology and team motivation. As one former CIA officer put it,

“There’s a lot of similarities between what I used to do in the Spy world and what you do in business.”

This isn’t just a catchy line—it’s a practical framework for anyone looking to lead, persuade, and adapt in high-stakes environments.

Recruiting Assets vs. Motivating Employees: The Psychology of Persuasion

At its core, recruiting an asset in the field is about understanding what drives people. In the CIA, officers spend months—sometimes years—learning what motivates their targets. Is it money, recognition, ideology, or something hidden beneath the surface? In business, the same principles apply. If you want to inspire your team, you have to know what truly matters to them. Incentives and recognition are obvious tools, but the real art lies in reading between the lines, spotting unspoken needs, and tailoring your approach. Research shows that leaders who master this psychology of persuasion build more loyal, high-performing teams.

The Power of Subtlety: Reading Between the Lines

Espionage is rarely about brute force. Instead, it’s about subtlety—catching the details others miss. In the transcript (7:40–7:54), the challenge of convincing someone to commit to a cause, even at great personal risk, is described as “a remarkable thing.” In business, subtlety means noticing when a competitor is vulnerable, or when a team member is struggling before it becomes a crisis. This kind of insight gives you a real edge. Studies indicate that organizations that recognize and address blind spots—both personal and organizational—gain a significant competitive advantage.

‘Getting Off the X’: Risk Management in a Chaotic World

One of the most powerful lessons from the field is the concept of “getting off the X” (1:22–1:24). In spycraft, this means moving out of harm’s way—fast—when things go wrong. In business, it’s about risk management and adaptability. Whether you’re facing a sudden market shift or a crisis within your team, you need to recognize danger quickly and act decisively. This survival skill, honed in operations, translates directly to thriving in today’s unpredictable corporate world.

The Recruitment Cycle: From Spotting to Letting Go

Recruitment in intelligence isn’t a one-off event; it’s a cycle—spotting, developing, nurturing, and sometimes letting go. The same applies to sales and team-building. You identify talent, invest in their growth, and, when necessary, make tough decisions about moving on. Interestingly, CIA officer-client relationships can last up to 20 years (1:24–1:28). That kind of loyalty is rare but possible when you apply these long-term leadership strategies to your own teams and clients.

The Ethics of Manipulation: Wise Engagement vs. Exploitation

Espionage walks a fine ethical line. In business, the psychology of persuasion must be balanced with integrity. Wise leaders engage and influence without crossing into destructive exploitation. Research suggests that ethical persuasion not only builds trust but also sustains long-term success.

Personal Story: The Spy Mindset After Betrayal

After being burned by a duplicitous business partner, applying a “spy mindset” can be transformative. You learn to spot red flags earlier, ask better questions, and protect your interests without becoming cynical. These lessons—rooted in risk avoidance, psychological insight, and enduring loyalty—can reshape your approach to leadership and team motivation, turning setbacks into strategic growth.

Data Table: Motivations Behind Betrayal in Espionage and Business

If you’ve ever wondered what really drives people to betray trust—whether in the shadowy world of espionage or the high-stakes arena of business—the answer is rarely what you expect. The motivation for betrayal isn’t always about grand ideals or political causes. In fact, as revealed in the transcript (12:01–12:36), the truth is often much simpler and, frankly, more human.

Comparing Motivations: Espionage vs. Business

Let’s break down the primary reasons for betrayal in both environments. You might assume that spies are motivated by ideology or patriotism, while business professionals are driven by career ambition. But research and real-world experience suggest otherwise. The spectrum of motivations is surprisingly similar, with a few key drivers standing out in both fields.

- Money: The top motivator, hands down. As the transcript points out,

“Money is a big one … sometimes it’s a very straightforward thing.”

Whether it’s a spy selling secrets or an employee leaking confidential data, financial incentive is the most common trigger.

- Family and Health: Sometimes, the motivation is deeply personal. Think of someone with a sick child who can’t get treatment in their home country (12:19–12:23). Desperation can override loyalty in both espionage and business settings.

- Ego: Feeling undervalued or overlooked is another powerful driver. The transcript (12:29–12:33) mentions those who “don’t feel like they got enough hugs from their employer.” That sense of disrespect or lack of recognition can push people to act against their organization.

- Resentment: Lingering grudges or perceived injustices—whether from a government or a corporate boss—often simmer until they boil over into outright betrayal.

- Ideology: Contrary to popular belief, ideology is rarely the real driver. The transcript (12:01–12:04) makes it clear: “It’s usually not ideology … not so much.”

Relative Frequency of Motivations

Based on anecdotal data and field experience, here’s how these motivations typically stack up:

- Money: 40%

- Ego: 20%

- Family/Health: 20%

- Resentment: 15%

- Ideology: 5%

It’s striking how closely these percentages align between espionage and business. The overlap is more than a coincidence—it’s a reflection of basic human psychology.

The Psychology of Persuasion: Spotting the Root Cause

So, what does this mean for you if you’re managing a team, running a business, or even conducting counterintelligence? The psychology of persuasion teaches us that identifying the real motivator is the key to pre-empting problems. If you can spot what’s driving someone—whether it’s money, ego, or something else—you’re in a much stronger position to address their needs before disloyalty takes root.

This is where business intelligence skills come into play. Recognizing personal motivators isn’t just about preventing betrayal; it’s also a game-changer for recruiting and retaining top talent or valuable assets. Research shows that both employees and intelligence assets respond best to timely recognition and practical incentives, not just lofty ideals or promises.

Strategic Advantage: Understanding Motivation

In both spying and business, understanding what truly motivates someone is the ultimate strategic advantage. The more you tune into these underlying drivers, the better equipped you are to build loyalty, trust, and long-term success—no matter which side of the table you’re on.

FAQ: Everything You Always Wanted To Ask (But the CIA Wouldn’t Confirm)

Curiosity about the world of espionage is only natural—especially when so many of its lessons apply just as much to business as to covert operations. In this section, we’ll tackle some of the most common questions people have about CIA tactics, asset recruitment, business intelligence skills, and the ethics in persuasion. Drawing from both expert commentary and real-world examples, let’s separate fact from fiction and see what spycraft can teach us about leadership and influence.

What’s the difference between a CIA officer and an agent/asset?

This is one of the most persistent misconceptions. In popular culture, the term “CIA agent” is thrown around, but in reality, CIA officers are the Americans who work for the agency. An agent or asset is the person who has been recruited—often a foreign national with access to valuable information (5:00–5:22). The officer does the recruiting and handling; the asset provides the intelligence. Understanding this distinction is fundamental to grasping how intelligence operations really work.

How do spies recruit assets in real life?

Asset recruitment is a methodical process. It starts with identifying what information is needed, then figuring out who has access to it (5:28–5:59). The next steps are spotting potential sources, developing a relationship, and—if the circumstances are right—recruiting them. This could be anyone from a deputy minister to a cab driver with unique access (6:14–6:26). The process is remarkably similar to business development: you identify targets, build trust, and offer incentives that matter to them.

What are the most common motivations for betrayal?

Contrary to what you might expect, ideology is rarely the main driver. Research and field experience show that money is the most common motivator, but personal grievances, a need for recognition, or even family emergencies can play a role (11:55–12:26). Sometimes, it’s as simple as someone feeling unappreciated by their employer or government. The key to successful asset recruitment—and business negotiation—is understanding these motivations and knowing how to address them ethically.

What makes a great asset handler (or business leader)?

Empathy, patience, and the ability to read people are crucial. You need to identify vulnerabilities, build rapport, and maintain trust over time (6:39–6:44). In both intelligence and business, the best leaders are those who can manage relationships and adapt to changing circumstances.

In what ways do spy tactics actually translate to sales?

Surprisingly, the overlap is significant. The art of persuasion, relationship-building, and understanding what drives people are all core business intelligence skills. As one expert put it,

“If you can sell the idea to somebody that they should commit treason on their country … that’s an incredible skill to use in business.”

(7:46–7:54) In sales, you’re not asking for treason, but you are asking people to make big decisions—often against their initial instincts.

Can you spot a spy in everyday life? Should you try?

In reality, most spies are trained to blend in. Trying to spot one is usually futile—and not recommended. Instead, focus on developing your own business intelligence skills: observe, listen, and analyze situations critically.

Are there ethical lines that shouldn’t be crossed—even in persuasion?

Absolutely. Both in espionage and business, ethics in persuasion matter. Exploiting someone’s vulnerabilities for personal gain crosses a line. The best asset handlers—and business leaders—succeed by building genuine trust and offering real value, not by manipulation.

In conclusion, the world of spycraft offers a fascinating lens on human behavior, motivation, and influence. Whether you’re in the boardroom or the field, the principles remain the same: understand people, build relationships, and always act with integrity.

TL;DR: In short: Espionage and business share more than you think. Whether it’s decoding motivations, assessing threats, or mastering persuasion, these skills can reveal a lot about today’s complex world — and possibly your place in it.

A big shoutout to The Diary Of A CEO for their thought-provoking content! Be sure to check it out here: https://youtu.be/7-ZCglrexbo?si=Qu8XLcXY-hht5hKm.